When a company no longer needs a well to support its oil and gas development, the well must be permanently sealed and taken out of service. This part of the closure process is known as “abandonment.”

Once a well is abandoned or a facility (such as a gas processing plant) is decommissioned, the land surface must be reclaimed.

Reclamation is a multi-year process to return the site to a state equivalent to the surrounding area and must meet certain regulatory requirements. Requirements include completing professional environmental site assessments, remediating any contaminated soil and/or ground water, replacing removed soil, and recontouring and revegetating the site. The final step in reclamation is an application to the regulator for approval.

The site is considered reclaimed once the regulator approves the reclamation.

From inception, oil and gas developments are designed with the end in mind. Reclamation planning starts in the early stages of resource development and, depending on the scope of the project, may include detailed plans in the regulatory application to initiate the project. Plans are frequently developed with input from local stakeholders and Indigenous communities.

Some oil and natural gas developments, including oil sands mines, have very long life cycles. To speed the reclamation process, many operators of these large sites have “progressive reclamation” – starting to reclaim a site even while some production activities are ongoing. Progressive reclamation establishes vegetation on part of a disturbed area no longer required for active operations.

Area-based closure is an approach that focuses on groups of proximate wells, rather than closing one well in one part of the province and another well hundreds of miles away, to increase efficiency and reduce costs, including environmental impacts.

Revegetation and more

Canadian oil and natural gas producers have active reclamation programs, including reclaiming wetlands. Research and monitoring are integral components of reclamation programs. Examples include:

Canadian Natural Resources area-based programs

Canadian Natural Resources Limited (Canadian Natural) has been using an area-based approach to advance revegetation and reclamation since 2013 to reclaim large contiguous areas. This program geographically groups well and pipeline abandonments, remediation and reclamation activities into projects. Project efficiencies are safely and strategically obtained through the coordination of people, equipment and technologies. In this way, sites are taken out of active resource production in a safe and environmentally-sound manner, while reducing reclamation costs and time. Through this area-based approach, Canadian Natural has abandoned over 10,000 inactive wells from 2018 to 2022.

Tree-planting programs

Planting a variety of trees, shrubs, and other vegetation is one of the final steps in the reclamation process. Vegetation helps retain moisture, reduce erosion, attract birds and wildlife, and provide nesting opportunities. Examples include:

- Imperial: Over 800 hectares in total have been reclaimed at their Kearl and Cold Lake operations. And Imperial has planted nearly 1.7 million trees and shrubs at their Cold Lake operations alone.

- Suncor: Around 1 million trees and seedlings planted in 2023.

- Canadian Natural: 1.6 million trees planted across all operations in 2022, bringing the total number of trees planted to 8.6 million

- Cenovus: Since 2016, Cenovus has planted more than 3.2 million trees as part of their reclamation and restoration programs and targets.

Ovintiv progressive reclamation

A critical part of oil and gas development is remediating and reclaiming temporary disturbances such as pipeline rights-of-way, well pad sites, and other ancillary sites that occur in the normal course of drilling, completing, and producing wells.

On provincial land in British Columbia, Ovintiv is shifting away from agricultural-based restoration to ecological-based restoration in ecologically sensitive areas.

This means maintaining coarse woody debris, active reforestation, and limited seeding of crop species to encourage the return of native species and forest-like conditions.

These practices better align the restoration with not only the needs and interests of Indigenous communities, but also with stakeholder and community expectations of wildlife and habitat restoration and the protection of sensitive areas.

Reclamation in the real world

Cold Lake Reclamation

An example of progressive reclamation can be found at Imperial Oil’s Cold Lake heavy oil development in Alberta. Progressive reclamation techniques are employed using native trees and shrubs that are traditional to Indigenous culture and medicine. And at several locations in Alberta and B.C., innovative reclamation techniques are being applied to linear disturbances such as roads and seismic lines to improve caribou habitat.

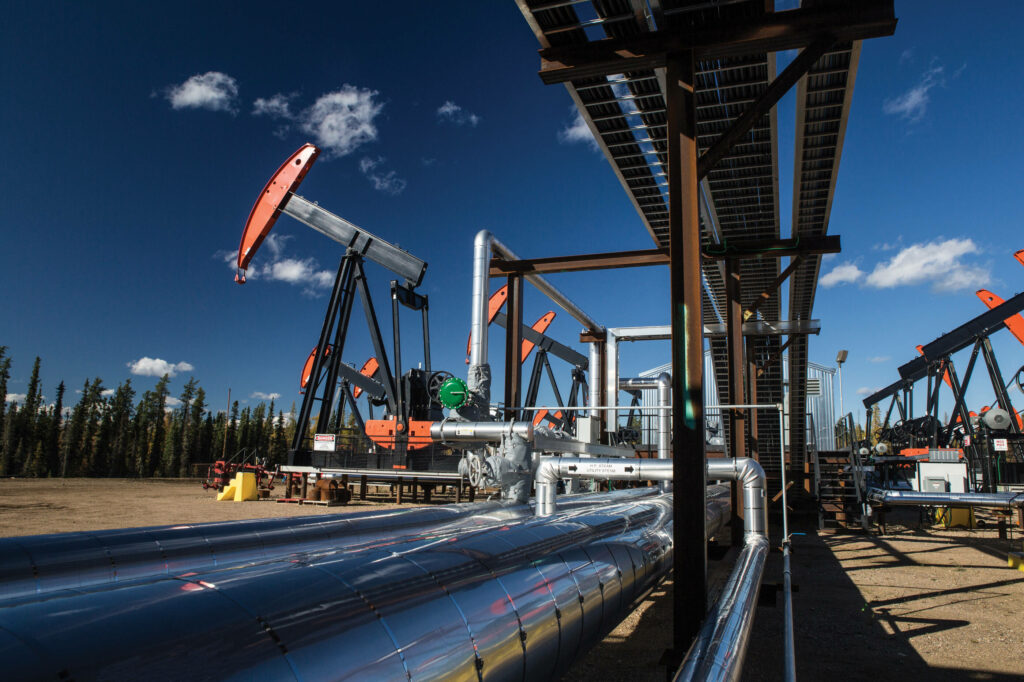

Image Source: Imperial Oil Ltd.

Life cycle of a well

The average life of a typical oil or natural gas well is 20 to 30 years.

The typical life cycle of a well is set out below:

- Active: A well that is currently producing oil or natural gas. Some wells are used to inject produced water back into the reservoir (water that comes to the surface along with oil or natural gas). When operating, injection wells are also considered active wells.

- Inactive: A well that has not produced (or injected) for a specific period of time, typically 12 months. The well may be re-activated if circumstances warrant.

- Suspended: A well that is in safely secured in accordance with regulatory requirements, usually with a temporary plug that can be removed. A suspended well can be re-activated if circumstances warrant.

- Abandoned: A well bore that is permanently plugged and the wellhead is removed. This process is also known as “decommissioning”, a term more commonly applied to facilities, including gas processing plants.

- Reclaimed: A former well site that has been remediated (contamination removed) if required and restored and approved by the regulator (i.e. received a reclamation certificate).

- Closed: A fully abandoned and reclaimed site for which the regulator has approved reclamation.

Every company that explores for and develops oil and natural gas in Canada is financially responsible for safely managing wells and infrastructure such as tanks and pipes throughout the entire life cycle.

Regulators in each province have specific liability management programs to ensure accountability throughout all stages of a well’s life cycle, up to and including reclamation.

Orphan wells and liability management

Active, inactive, suspended, and abandoned wells and facilities are managed by the well owner (operator), including all costs. Wells and associated infrastructure may be designated as “orphan” by the provincial regulatory when the operator is insolvent, bankrupt, or cannot be located.

The cost of abandoning and reclaiming orphan infrastructure is funded collectively by producers through provincial orphan funds that collect orphan well levies. The orphan levy is determined by the regulator that considers the number of orphan sites and other factors, including the cost per site and the time needed to reclaim the sites.

Liability management programs are overseen by provincial regulators and are intended to ensure operators are responsible for costs throughout the life of a well or facility, including closure (i.e. decommissioning, remediation, and reclamation).

B.C., Alberta, and Saskatchewan have modernized their liability management programs through revised or new legislation, guides, and directives. An element of this are orphan programs funded by operators to ensure that industry, not taxpayers, pay to abandon and reclaim orphan infrastructure.