On this page you’ll find general information about the Canadian oil sands. For information oil sands, visit Pathways Alliance.

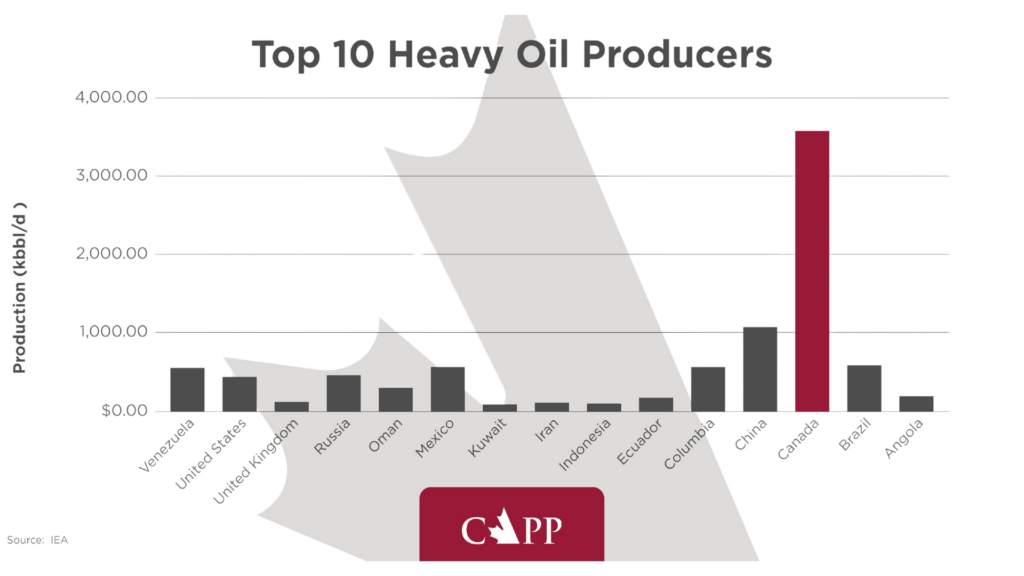

With estimated reserves of about 164 billion barrels, the Canadian oil sands are among the largest oil deposits on the planet. They are so large that Canada ranks third behind Venezuela and Saudi Arabia in terms of oil reserves. The oil sands are a significant part of Canada’s oil production. In 2023, about 58% of all production was from the oil sands.

Where are Canada’s oil sands?

Canada’s oil sands are primarily in northeastern Alberta (Athabasca), with additional heavy oil deposits in northwestern Alberta (Peace River) and the Cold Lake / Lloydminster region in Alberta and Saskatchewan. The main oil sands region covers an area of about 142,000 square kilometres (km2).

What makes the oil sands unique?

Oil sands deposits are a mixture of sand and clay, water, and a kind of oil called bitumen – oil that is too thick to flow on its own. At room temperature, bitumen is like peanut butter or cold molasses. At low temperatures, oil sands oil is as hard as a hockey puck.

This means Canada’s oil producers had to develop novel ways to extract the oil. Initially, oil sand was recovered exclusively through mining. But in recent decades, recovery methods have changed. Producers can now recover bitumen from oil sands deposits that are deeper while disturbing significantly less land. In fact, with new technologies and recovery techniques, the Government of Alberta estimates just 3% (about 4,800 km2) would be disturbed by surface mining, as most bitumen is now recovered using in situ methods. (Source: Oil Sands Facts and Stats)

About 4,800 km² of surface mineable area make up roughly 3.4% of all Alberta oil sands.

Recovering the oil sands

Bitumen is recovered from oil sands deposits using two main methods: surface mining and in situ. The method depends on how deep the oil sands deposits are below the surface.

Surface mining is used when the oil sands deposits lie within 70 meters (200 feet) of the earth’s surface. About 20% of oil sands deposits are close enough to the surface to be mined. Large shovels scoop oil sands into haul trucks that transport it to crushers where large clumps are broken down. The oil sands are then mixed with hot water and pumped to a plant called an upgrader where the bitumen is separated from the other components such as sand, clay, and water. These other components, called “tailings”, are managed separately.

In situ methods are needed to produce bitumen from deeper deposits. About 80% of all oil sands deposits are in situ. “In situ” means “in place,” because bitumen is separated from the sand and water below ground, right in the deposit itself. This is done by heating the bitumen so it becomes fluid enough that it can be pumped to the surface. There are two main methods used for in situ production: steam-assisted gravity drainage (SAGD) and cyclic steam stimulation (CSS).

Oil sands surface mining

In situ production – SAGD

In situ production – CCS

In SAGD production, two wells are drilled into the bitumen deposit. The upper injection well is drilled vertically into the deposit, then turned 90 degrees and drilled horizontally. A second well, the production well, is drilled deeper than the first and parallels the horizontal portion of the first well. Steam is injected into the deposit through the upper well. Heated bitumen begins to move by gravity down toward the second well. Pumps in the second well draw the bitumen into the well and up to the surface. Multiple well pairs can be drilled from a single surface location, which reduces surface disturbance.

The CSS method injects steam into a single well to heat and liquefy the bitumen, which is then pumped to the surface through the same well. This cycle is repeated until most of the bitumen is produced.

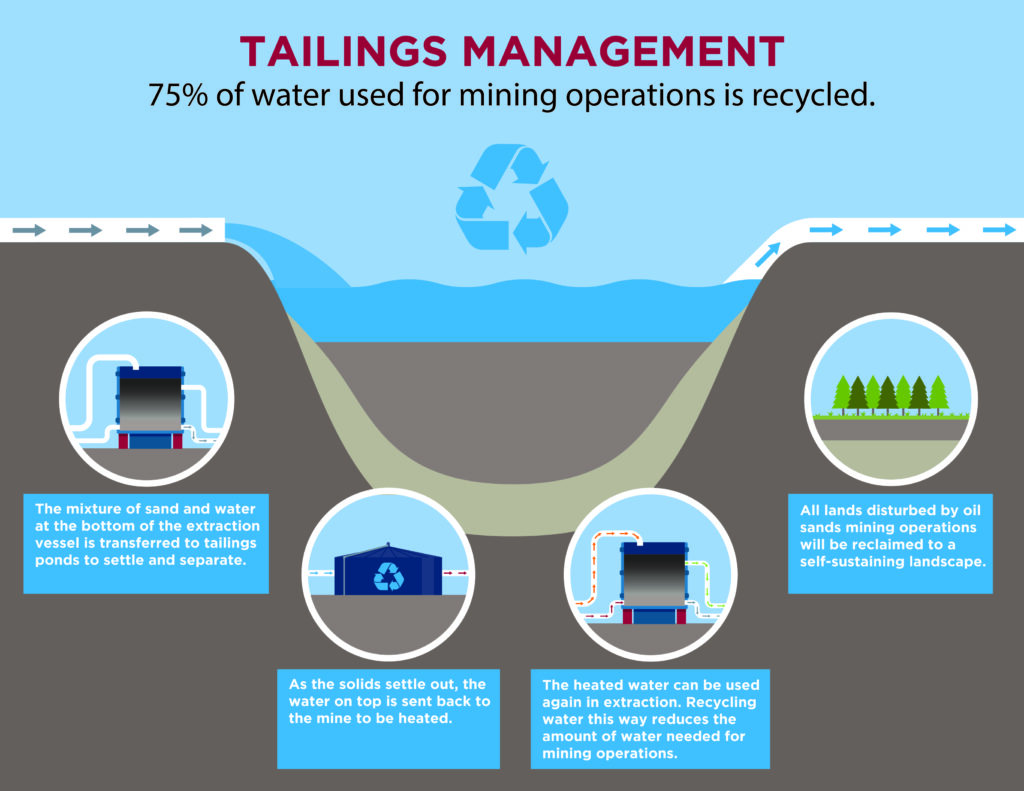

Both SAGD and CSS use large volumes of water and must burn natural gas to create steam that is injected into the oil sands deposit. New research is leading to technologies that reduce or eliminate the need for water (steam) and natural gas. (Link to water use) Oil sands producers have worked hard to reduce water use especially through recycling water used in various operations, reducing the need to withdraw fresh water from rivers and other surface water sources.

Once extracted, raw bitumen is mixed with lighter hydrocarbons to make “dilbit”, a substance that flows through a pipeline to refineries in Alberta, elsewhere in Canada, and the U.S. Bitumen may also be upgraded (refined) to make synthetic crude oil (SCO), which is transported by pipeline to refineries in Canada and the U.S. or exported to international customers. SCO can be further refined to make gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, and other petroleum-based products.

Oil sands tailings

In oil sands mining operations, the by-product of the extraction process used to separate oil from sand and clay is called “tailings”. Tailings are composed of a mixture of water, sand, clay, and residual bitumen.

Tailings are deposited in temporary storage ponds. Tailings ponds allow operators to recover most of the process water and reuse it in operations. Once the remaining sand and clay settle in the ponds, they can be stored and used when the land is ready to be reclaimed.

Tailings ponds are not unique to the oil sands – they are used around the world in mining and other industrial processes.

“Oil Sands” not “Tar Sands”

The oil sands resource is sometimes referred to as “tar sands,” but that term is incorrect because bitumen and tar (asphalt) are different substances. The term “oil sands” is correct because it identifies the end product derived from bitumen, which is oil not tar.