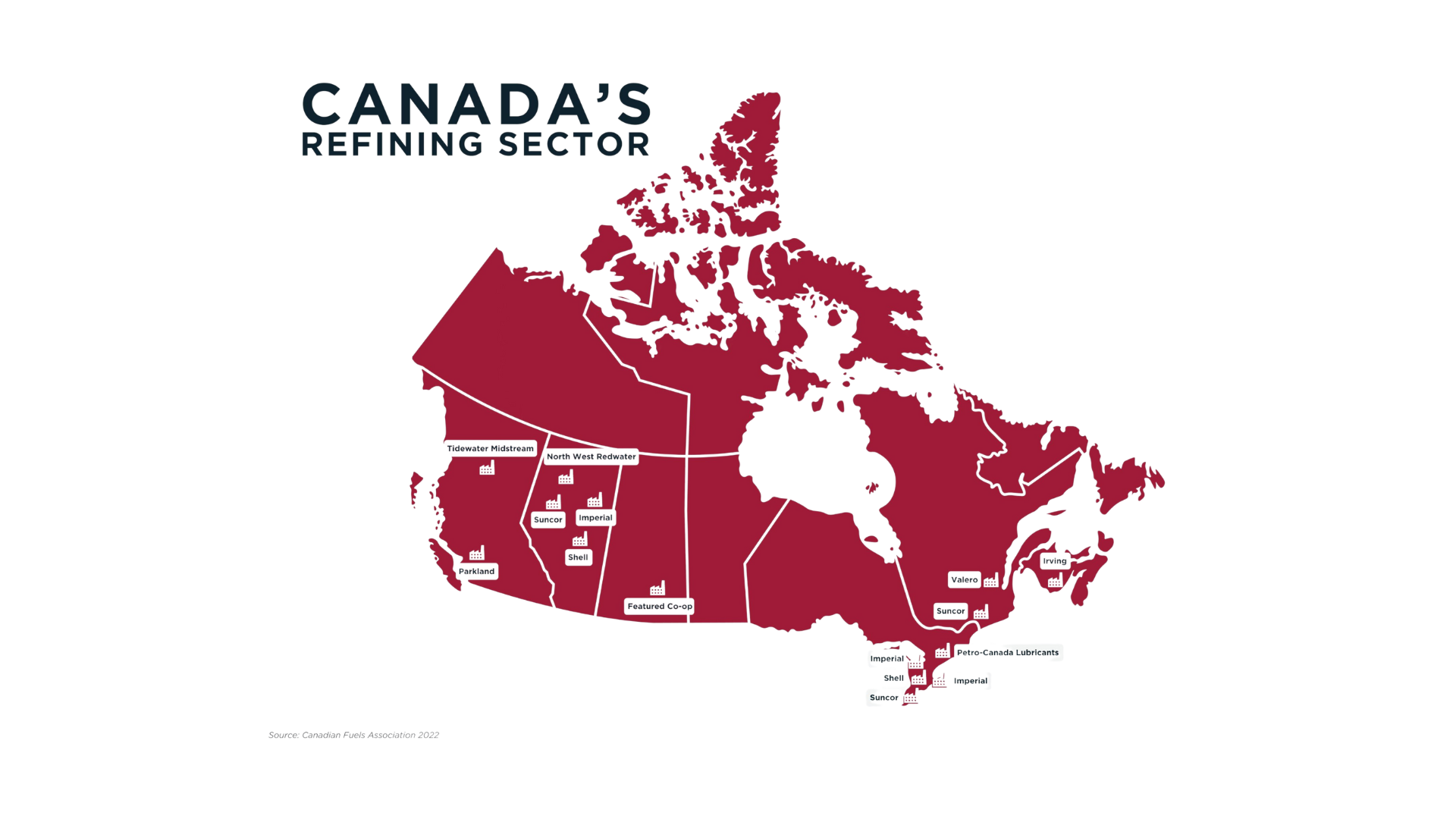

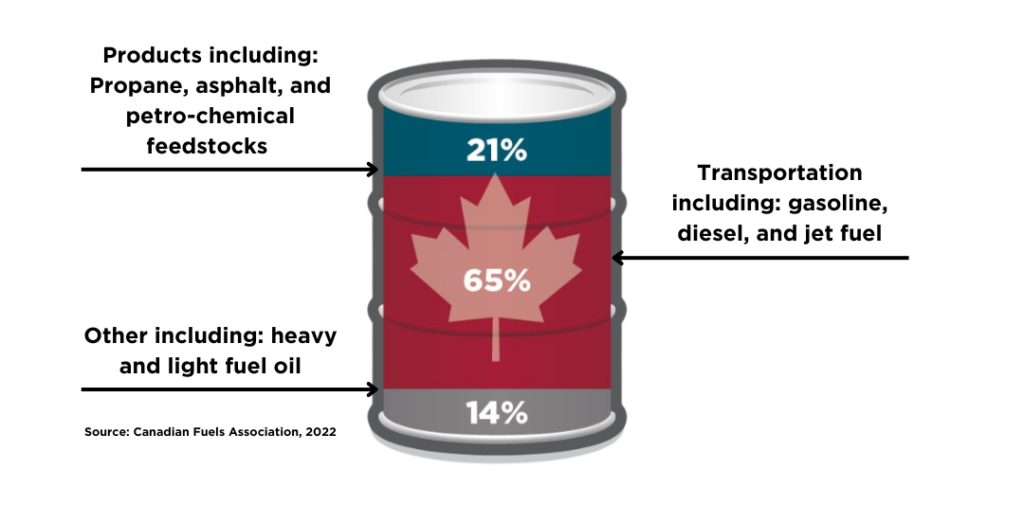

Refineries turn crude oil into usable products. These include transportation fuels – gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel – plus other materials such as asphalt for roads and petrochemicals for making other products. There are 14 refineries in Canada that have a collective crude oil refining capacity of 2.0 million barrels per day (b/d). (Source: Canadian Fuels Association).

Most Canadian oil is used for transportation, essential for moving people and goods. Crude oil can be refined to make these transportation fuels:

- Gasoline: designed for internal combustion engines, commonly used in cars and light-duty trucks.

- Diesel: designed for engines commonly used in trucks, buses and public transport, locomotives, and farm and heavy equipment like bulldozers. Diesel contains more energy and power density than gasoline.

- Aviation fuels: specialized fuels used to power various types of aircraft for travel and shipping.

Oil and natural gas are also the building blocks for numerous other products:

- Plastics and other petroleum-based products are used in electronics. From speakers and smartphones to computers, cameras, and televisions, most electronics have components derived from oil.

- Clothing can be made from petroleum-based fibres including acrylic, rayon, polyester, nylon, and other materials. Some shoes and purses use petrochemicals for their lightweight, durable, and water-resistant properties.

- Sports equipment including basketballs, golf balls and bags, football helmets, surfboards, skis, tennis rackets, and fishing rods can contain some petroleum-based material.

- Many personal care products can be derived from petroleum including perfume, hair dye, cosmetics (lipstick, makeup, foundation, eyeshadow, mascara, eyeliner), hand lotion, toothpaste, soap, shaving cream, deodorant, and shampoo.

- Modern health care relies on petroleum. Plastics are used in a wide range of medical devices and petrochemicals for pharmaceuticals (drugs). Products include hospital equipment, IV bags, aspirin, antihistamines, artificial limbs, dentures, eyeglasses, contact lenses, hearing aids, heart valves, and many more.

- Many household products are made with petroleum. From construction materials such as roofing and insulation to flooring, furniture, appliances, pillows, curtains, rugs, and paint. Even many everyday kitchen items including dishes, cups, non-stick pans, and dish detergent can be created from oil products.

- Natural gas is commonly used as a feedstock to produce two nitrogen-based fertilizers – ammonia and urea.

- Canada’s roads depend on high-quality asphalt that is produced from oil.

Did you know the average barrel of oil does much more than just put gasoline in your car?

Oil and petro-chemicals are used to create a wide range of products, including:

- Electronics

- Textiles

- Sporting Goods (eg. golf balls, helmets, surfboards)

- Health & Beauty Products (eg. soaps, contact lenses)

- Medical Supplies

- Household Products (eg. paint, pillows, non-stick pans)

Petroleum in real life: Money

Money. It is ubiquitous – used daily around the world to facilitate the exchange of goods and services. Virtually every nation has created its own currency, both coins and notes of various denominations. A nation’s currency is tied to national identity, often portraying a country’s most iconic figures, national symbols, and other elements that uniquely identify the nation. The latest trend in hard currency is in polymers: plastic bank notes.

Canadians formerly used bank notes made of paper and cotton. In 2011, the Bank of Canada introduced bank notes made from a synthetic polymer called polyethylene terephthalate or PET, a petrochemical derived from oil and natural gas. Polymer bank notes last up to four times longer than paper and, due to the unique properties of PET, it’s possible to embed more security features than in paper notes to prevent counterfeiting. Canadian money has several unique security features. Not only does the polymer have a distinct feel, but the plastic material also allows for the inclusion of a nearly clear window (an unprinted area of the polymer), a hard-to-copy hologram, raised ink, hidden numbers, and detailed design elements that are very crisp.

While plastic bank notes are initially more expensive to print than paper bills, plastic bills enjoy a longer life cycle, which means we’ll print fewer bills over the long run. And fewer bills translate to positive environmental benefits. The Bank of Canada has advised that over their entire life cycle, polymer bills are responsible for 32% fewer greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and a 30% reduction in energy compared to making paper notes.

Petroleum in real life: Ski and snowboard equipment

Outdoor enthusiasts have various choices when it comes to ski and snowboard equipment. Winter sport gear must be safe and strong while still flexible and promoting optimal performance on the slopes. That’s why vital parts of ski and snowboard equipment are made from plastics derived from petroleum.

Even though snowboards, helmets, and goggles may be relatively new to the party, skis have been around since prehistoric times – with the first fragments of ski-like objects dating back to 6000 BC. The first modern-day skis were used in the 1760s by Norway’s military during shoot / ski exercises, precursors to today’s biathlon. These early skis were made from solid wood, while ski boots were fashioned from leather.

In the 1950s, metal and then plastic skis were introduced by ski enthusiast Howard Head; plastic boots arrived in the 1960s. These were favoured because the equipment was lighter and faster. Also, plastics enabled the creation of lightweight helmets and high-performance goggles, which are vital safety gear.

Petroleum in real life: propane

(Image source: Canadian Propane Association)

Propane is a portable fuel derived from natural gas processing or oil refining. Propane is both clean and versatile, with lower greenhouse gas (GHG) and particulate emissions than many other carbon-based fuels. When combusted, propane produces water vapour and carbon dioxide.

While most of us think of propane as fuel for our backyard barbecues, propane has many other applications. It is used for cooking, operating household appliances, and to operate buses, vans, and fleet vehicles. It’s used by restaurants to heat patios in cold weather. It’s also used widely in agriculture for barn heating, powering irrigation systems, and grain drying, and in industry for mining operations, metal processing, and construction heating.

In Canada, propane is widely used in rural and remote areas, where it can be the only energy source for communities that aren’t connected to an electrical grid or to natural gas distribution.

Propane’s end-use GHG emissions are significantly lower than gasoline, diesel, coal, and heating oil. Propane emits up to 26% fewer GHGs than gasoline, 38% fewer GHGs than fuel oil in furnaces, and half the carbon dioxide emissions of charcoal used in barbecues. Propane emits 60% less carbon monoxide than gasoline, 98% less particulate matter than diesel, and contains virtually no sulphur (a contributor to acid rain) or soot. (Source: Canadian-made low-carbon energy – Canadian Propane Association)

In the event of a leak, propane becomes a vapour that does not contaminate soil, air, or aquifers. And as it is not itself a greenhouse gas, it has no impact on the atmosphere if accidentally released.

Approximately 50% of the propane produced in Canada is used domestically while the remainder is exported. (Source: Economic Impact – Canadian Propane Association)

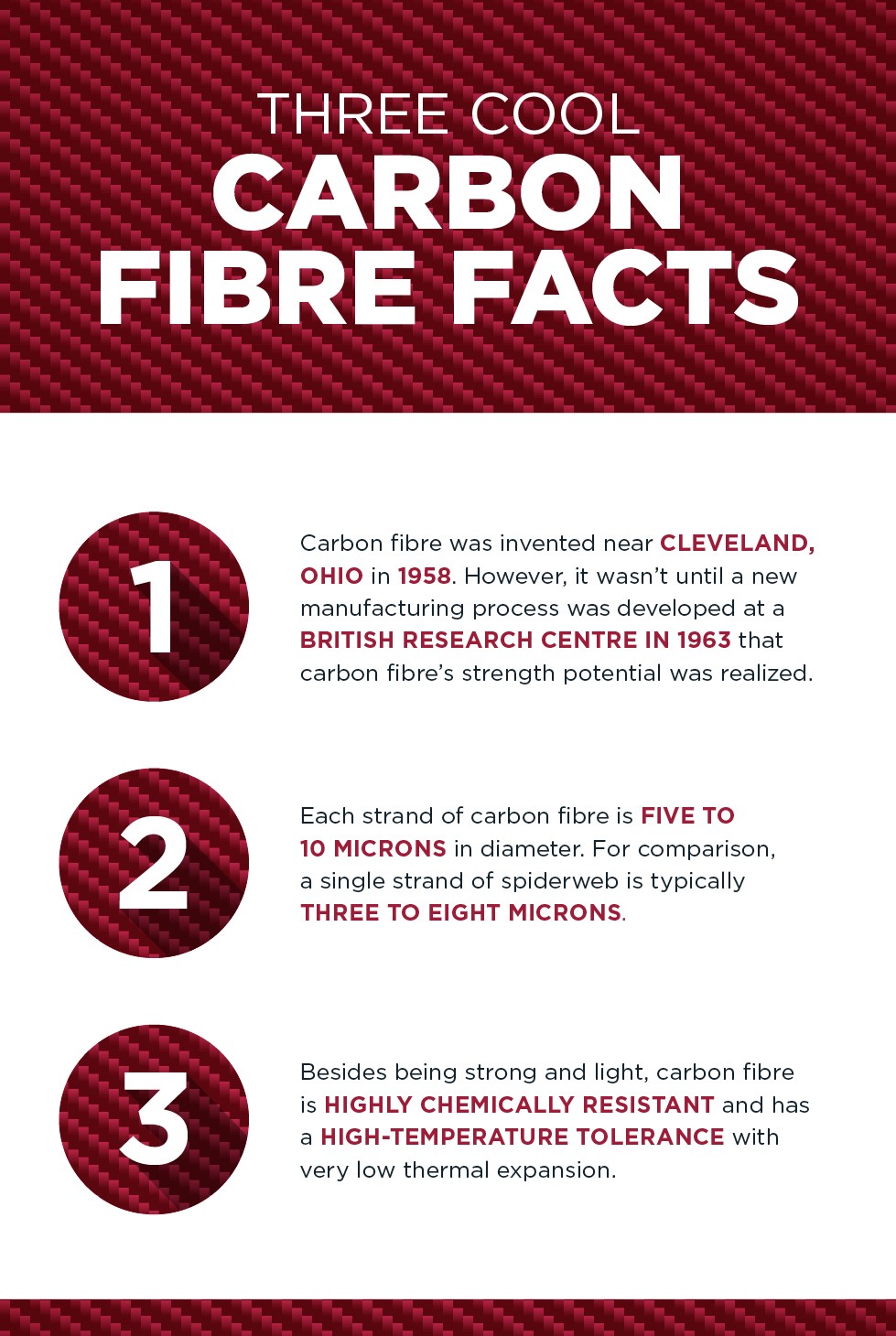

Petroleum in real life: carbon fibre

Carbon fibre is a versatile and common material is used to make airplanes, boats, golf clubs, speakers, X-ray equipment, wind turbines, bikes, cars, valves, seals, and pumps. It’s even used for surgical repair of tendons and ligaments. Carbon fibre is wide used because it’s both lightweight and strong.

Carbon fibre is made from strands of carbon thinner than a human hair. It gets its strength when those filaments are twisted together like yarn, then woven like cloth to make a sheet of carbon that can be laid over a mold and coated in resin or plastic to take on a permanent shape.

Carbon fibres are made from polyacrylonitrile, which in turn is manufactured from polymers and acrylonitrile – both among the 6,000 useful products that come from petroleum. Making carbon fibre is complicated – the process is partly chemical, partly mechanical. The precise composition of each carbon fibre material varies from one manufacturer to another.

One of carbon fibre’s biggest advantages is how light it is compared to many other materials, which can result in lower greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. For example, many vehicle components are made from steel, but replacing steel components with lighter carbon fibre can reduce the weight of an average car by up to 60%. (Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration) A lighter vehicle burns less fuel – by up to 30%, cutting GHG emissions by up to 20%. (Source: Oak Ridge National Laboratory)

Petroleum in real life: food, fertilizer, and fuel

The relationship between oil and natural gas and the food we eat goes beyond the trucks, ships, planes, and trains that carry food from farms to grocery stores. Large-scale food production would not be possible without synthetic fertilizers made from oil and natural gas feedstocks.

According to the John Hopkins Center for a Livable Future, “of all the innovations in agriculture, arguably none has been more influential than synthetic fertilizers.”

Nitrogen, together with phosphorous and potassium, is one of the macro-nutrients required for plant growth. Natural gas is commonly used as a feedstock to produce two nitrogen-based fertilizers – ammonia and urea – in large quantities. These are then mixed with other ingredients, mainly phosphorus and potassium, to manufacture a range of synthetic fertilizers.

Two key advantages of synthetic fertilizers: these nutrients are easily available to plants by virtue of solubility, or their ability to slowly release active ingredients to provide an ongoing nutrient supply. Both these properties can be highly desirable to farmers, as the former creates immediate growth response in the crop, and the latter has longer-term benefits with less frequent application.

Petroleum in real life: pills

First synthesized in 1897 by German chemist Felix Hoffman, aspirin has proven to be a safe and reliable medicine. World-wide, people swallow an estimated 58 billion tablets a year to treat pain, fever, and inflammation, and to reduce heart conditions or stroke.

Aspirin’s main ingredient is acetylsalicylic acid, which is made via a chemical reaction involving the petrochemicals cumene, phenol, and benzene. Aspirin is only one of the numerous medications made from petrochemicals. Many over-the-counter (OTC) and prescription drugs and medicinal products are made with the help of petrochemicals, including antihistamines, antibacterials, suppositories, cough syrups, lubricants, creams, ointments, salves, analgesics, and gels such as hand sanitizers.

Most pharmaceutical drugs are made through chemical reactions that involve the use of organic molecules. Petroleum is a source of organic molecules used in the drug manufacturing process. Even drugs that come from natural sources like plants are still often purified using petrochemicals, resulting in a more efficient and less costly manufacturing process. Others, like antibiotics derived from natural fungi and microbes – namely, penicillin – often use phenol and cumene as preparatory agents. Finally, pill capsules and coatings are frequently polymer based. In fact, time-release drugs depend on a tartaric acid-based polymer that slowly dissolves, administering just the right dose of medication.

Petroleum in real life: contact lenses

More than 150 million people across the globe wear contact lenses, these discreet vision enhancers that would not be possible without oil.

The earliest contact lenses were made using blown glass, making them heavy and uncomfortable. Worse, they covered the entire eye and didn’t allow oxygen to pass through, effectively suffocating the eye. Wearers would complain of excruciating eye pain after a few hours of use.

Things improved in the 1930s when new plastics made it possible to produce lightweight contact lenses. In 1948, the invention of the corneal contact lens that covers only the cornea, again improved eye health and wearability. Then in 1953, Czech chemist Otto Wichterle invented a new type of plastic called hydrogel. It could be shaped and molded like other plastics. But it also could absorb up to 40% of its weight in water to become soft and pliable when wet: the perfect material for a comfortable-to-wear contact lens. In the 1960s, Bausch and Lomb developed a process to mass produce ‘soft’ contact lenses.

There are two types of contact lenses: soft lenses and rigid gas-permeable (RGP) lenses, commonly called hard lenses. Soft lenses are the most popular, with about 80% of the market.

For both types, polymers are a key ingredient. A polymer is a chain-like molecule made by combining many small molecules called monomers. Some polymers are natural – think proteins, cellulose, and starch. Other polymers are human-made, produced by complex chemical reactions termed polymerizations. And they’re everywhere, from bike tires to television remotes to fibres for clothing to contact lenses.