Canada’s oil and natural gas deposits were formed over millions of years, as tiny sea creatures and plants died and drifted to the sea floor, to be covered by layers of sand and other sediment. Over time, pressure and temperature transformed the organic matter into oil and natural gas.

Conventional oil

Conventional oil recovery uses drilling rigs and is the production method most people are familiar with. The traditional pumpjack is often the image associated with conventional oil recovery.

Oil is a black, brownish or amber liquid that is a complex mix of elements including carbon, hydrogen, sulphur, nitrogen, oxygen and metals. Oil can be classified as light, medium, heavy, or extra heavy.

- Light and medium oil can flow naturally and is generally produced (extracted) using drilling and pumping – this includes Canada’s offshore oil. Some light oil is trapped in “tight” (non-porous) rock formations, usually shale. This “light tight oil” can be recovered using hydraulic fracturing.

- Heavy oil is thick and does not flow easily, often requiring advanced technology to produce. Heavy oil deposits are found in Alberta and Saskatchewan in the Cold Lake and Lloydminister areas.

- Bitumen is the kind of oil found in the oil sands – is extra-heavy and is too thick to flow without being heated or thinned (diluted) with lighter hydrocarbons.

Natural gas

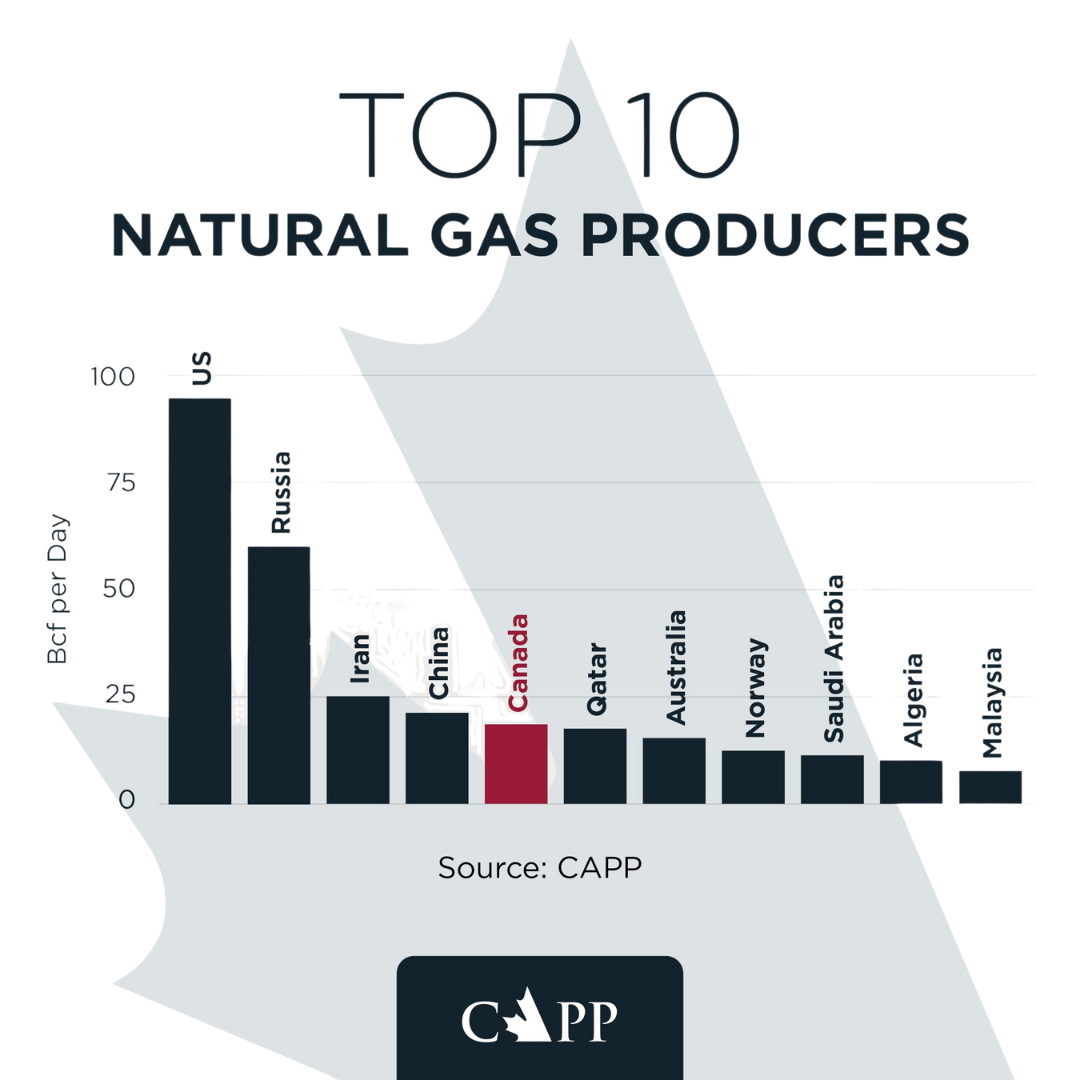

Natural gas is mostly methane, but also contains other compounds such as ethane, propane, butane, and pentanes. Canada currently produces 17.3 billion cubic feet of natural gas per day.

How much oil and natural gas does Canada produce?

About 95% of Canada’s oil production (including the oil sands) and all current natural gas production occurs in the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin (WCSB), which spans the provinces of British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. Oil is also produced offshore from Newfoundland and Labrador.

In 2022, total Canadian production of natural gas was 17.3 billion cubic feet per day (Bcf /d). (Source: CAPP)

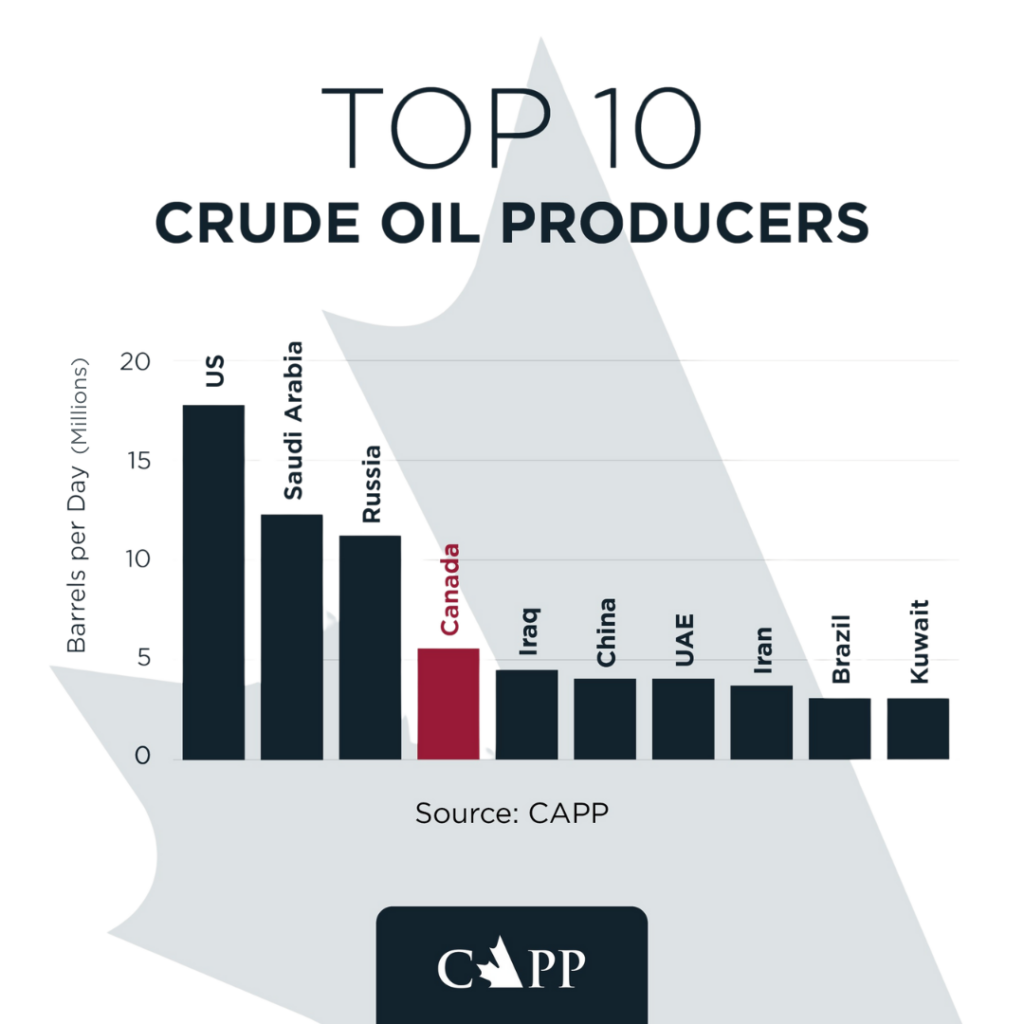

In 2022, Canadian oil production totaled 5.5 million barrels per day, including:

- Oil sands – 3.2 million barrels per day (MM b/d) or about 58% of Canada’s total production.

- Conventional (non-oil sands) – 1.5 MM b/d or about 27% of Canadian total production

- Offshore – 0.2 MM b/d or about 4% of Canadian total production.

- NGLS (Natural Gas Liquids) – 0.6 MM b/d, at 11% of production

The oil and natural gas industry is divided into three separate but connected sectors:

- Upstream – exploration and production of both oil and natural gas, including offshore, conventional, and oil sands.

- Midstream – transporting, processing, and storing oil and natural gas, including pipelines, natural gas processing plants, and storage hubs.

- Downstream – refining oil into final products like gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, and petrochemicals, then distributing those products to final consumers. Downstream facilities include refineries and petrochemical plants.

Canada’s oil sands

With estimated reserves of about 164 billion barrels, the Canadian oil sands are among the largest oil deposits on the planet. They are so large that Canada ranks third behind Venezuela and Saudi Arabia in terms of oil reserves. The oil sands are a significant part of Canada’s oil production. In 2023 about 58% of all production was from the oil sands.

Markets and transportation

Canada produces more oil and natural gas than we need to meet energy demand within our country, so the remainder is exported. Currently, most of Canada’s oil and natural gas exports go to the United States. New Canadian infrastructure such as the Trans Mountain Expansion Project pipeline, and liquefied natural gas (LNG) facilities on the West Coast, will enable Canada to reach new markets such as China, India, and other destinations in the Asia-Pacific region.

Oil and natural gas are transported by pipelines, rail, marine shipping, and trucking. The safe transportation of resources is a top priority and operators are committed to the prevention of environmental incidents.

LNG

Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) is natural gas that has been super cooled to -162° C to become a liquid. Being in a liquid state allows for the gas to be transported to global markets via LNG carrier.

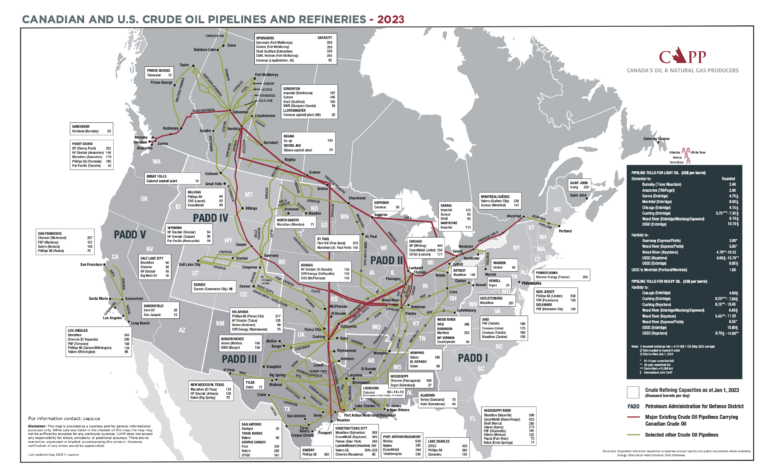

Pipelines

Pipelines are a safe, reliable, and economic way to transport oil and gas.

- Upstream pipelines include gathering and feeder lines that collect oil and natural gas from multiple wells or production sites and transport them to processing facilities or main transmission lines.

- Midstream pipelines transport oil and gas to refineries, distribution points, or export terminals.

- Downstream pipelines include refined product pipelines (eg. gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel) that transport from refineries to distribution terminals, and natural gas distribution pipelines which deliver gas to homes, businesses, and industries from facilities to local distribution networks.

Pipelines are a critical part of Canada’s transportation infrastructure. Pipeline transportation is a safe, efficient and economic way to move large volumes of oil and natural gas. Throughout the entire life cycle of a pipeline, safety and environmental protection are top priorities. The entire process is strictly regulated.

Canada’s pipeline system is made up of four main types of pipelines that gather, transport, and deliver energy to Canadians and to export markets in the United States. Pipelines that cross provincial or international borders are regulated by the Canadian Energy Regulator (CER) within Canada. Smaller pipelines within each province are under provincial jurisdiction.

Oil and natural gas pipelines are typically made of coated steel pipe that is normally buried underground (in the far North and in thermal operations, pipelines are built above ground due to permafrost – these above-ground pipelines are insulated).

Natural gas pipelines have above-ground compressor stations at intervals along the route to maintain pressure inside the pipeline. Crude oil or liquids pipelines have above-ground pump stations along the route to keep the pipeline’s contents moving.

Operators have options for building pipelines over, through, or below water. Sometimes a tunnel is drilled underneath the river or water body and the pipeline is pulled through. A pipeline can be suspended above a waterway, similar to a bridge. Pipelines can also be laid on the lakebed or riverbed and anchored in place. The pipeline is monitored during and after construction.

Canada’s offshore sector

About 4% of Canada’s oil production comes from four developments offshore Newfoundland and Labrador: Hibernia, Terra Nova, White Rose, and Hebron.

Refineries

There are 14 refineries in Canada and they have a collective crude oil refining capacity of 2 million barrels per day (b/d).

Refineries turn crude oil into useable products such as transportation fuels – gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel – plus other materials such as asphalt for roads and petrochemicals for making other products. Most Canadian oil is used for transportation, essential for moving people and goods. Crude oil can be refined to make these transportation fuels:

- Gasoline – designed for internal combustion engines, commonly used in cars and light-duty trucks.

- Diesel – designed for engines commonly used in trucks, buses and public transport, locomotives, and farm and heavy equipment like bulldozers. Diesel contains more energy and power density than gasoline.`

- Jet fuels – specialized fuels used to power various types of aircraft.

Mineral rights

Who has the right to develop Canada’s oil and natural gas resources?

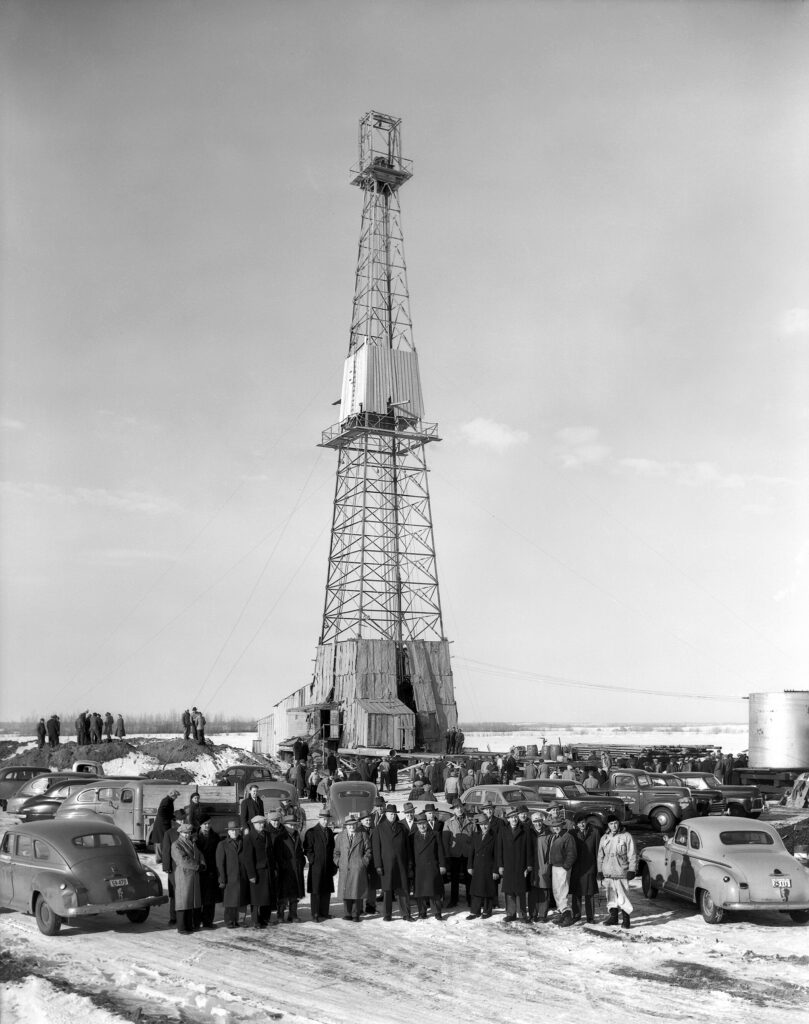

Our energy history

Canada has a long history of oil and natural gas exploration and development.